The Thames Torso Murders

Disclaimer: this article contains details which may be upsetting for some readers. Discretion is advised.

The UK is the home of one of the most notorious serial killers to have walked the streets, and perhaps the person who started the morbid curiosity that many of the public have with true crime. If you asked the person sitting next to you on the train or the bus whether they’ve ever heard of Jack the Ripper, I’m sure that most people would say ‘yes’. He has been made all the more infamous by the fact that he was never caught, nor was he formerly identified. The gruesome tales of his five known victims, to this day, hold such intrigue that London is still host to Ripper walking tours, books claiming to know the identity of 'Leather Apron' line the shelves of stores, and many televised documentaries are widely available online and on the screen.

Image 1: a newspaper depiction of the discovery of one of Jack the Ripper's victims by local police officers.

But if you then asked the person sitting next to you whether they’ve ever heard of the Thames Torso murders, I suspect you might receive more of a mixed response. The murders occurred around the same time as Jack was rampaging around Whitechapel, and yet the fascination with the notorious serial killer was such that the news of a second serial killer stalking the streets was pushed far back in the pages of the daily newspapers. Reports of body parts found floating in the Thames paled to the public in comparison to stories of prostitutes and a murderer stalking the streets of Whitechapel after dark.

The Thames Torso murders is a title which encompasses the discovery of four female bodies across districts of London between 1887 and 1889. Despite the best efforts of the police and doctors at the time, only one of these bodies would be identified – the other three remain nameless to this day. There's a chance, however, that the Thames Torso Murder cases could stretch further than what history refers to as the 'canonical four' - links have been made between the four known victims and other similar cases. For now, though, we're going to focus on the four victims most associated with this brutal period between 1887 and 1889.

The Rainham Mystery

The first discovery occurred on the 11th May 1887 in the river Thames near Rainham, a locality on the far east side of London. A lighterman by the name of Edward Hughes would have his curiosity peaked by the sight of a bundle floating in the water next to his canal barge. Curiosity would change to horror when he went on to open the canvas bag only to face the sight of a human torso - the head, limbs and breasts of which had been amputated.

An article in London’s Weekly Dispatch dated Sunday 24th July 1887 would report that further remains would be found over subsequent weeks at locations including the Thames off Temple Pier, the foreshore of the river off Battersea Pier, and in Regent’s Canal. The newspaper listed the found body parts as follows: ‘remains comprising the arms (divided), the lower part of the thorax, the pelvis, both thighs, and the legs and feet; in fact, the entire body, except the head and the upper part of the chest, - have all been recovered and are now in the possession of the police authorities.’ According to the article, the parts of the body which had been found early in May had already been interred in a cemetery in Ilford, and these were subsequently exhumed when further body parts were discovered. Despite the advanced stage of decomposition of the formerly interred body parts, all portions were gathered together and it was confirmed that they all originated from the same victim.

Image 2: map of locations where the Rainham victim's body parts were located

The body parts were closely examined by a police surgeon who assessed that the victim had been dismembered with anatomical skill, although the potential that the body parts had been dismembered for medical practice – such as by students at a medical college – was ruled out. The assessment of general practitioner and surgeon Edward Callaway was that the remains belonged to a woman between the ages of 27 and 29 years. She was reported to be approximately 5ft 3in (although various newspaper articles would state that this was closer to 5ft 4in), described as ‘stout’ and ‘well-nourished’, and probably with dark hair. It was ascertained that she had never had children.

Dr Edward Callaway believed that the victim had died towards the end of April, or perhaps at the beginning of May 1887, and he felt it likely that the victim had been dismembered very shortly after her death.

Evidence in this case was incredibly sparse – despite the description provided by the medical experts, the victim was unable to be identified and a cause of death could not be ascertained due to the incomplete physical form. Police conducted extensive enquiries in a bid to find out who the victim was, but were unable to reach a likely conclusion.

When the case eventually went to inquest, the jury were instructed to reach a verdict of simply ‘found dead’. This case would go on to be referred to simply as the Rainham mystery, and would form the first of what would go on to be dubbed the ‘canonical four’ of the Thames Torso Murders.

The Whitehall Mystery

Image 3: map of the location of Whitehall in comparison to Whitechapel

If police had hoped that the dismembered body found in Rainham had been a one-off discovery, 11th September 1888 would show that they were gravely mistaken. Jack the Ripper had already commenced his rampage through Whitechapel when Frederick Moore, a local labourer, made the gruesome discovery of a dismembered right arm and the edge of the shoulder, wrapped in newspaper, on the banks of the Thames near Whitehall.

If you’re not local to London, it’s worth being aware that Whitechapel and Whitehall are two separate locations. Like most cities, London is divided into districts, with Whitechapel being a district located slightly to the north-east of the city centre. Whitehall is an area just south-west of the city centre (see map to the right).

Today, Whitehall is located in the London district of Westminster, with Trafalgar Square located a few hundred metres to the north and Downing Street tucked off the main road. If you’re using Tower Bridge as a landmark, Whitechapel is to the north, with Whitehall being a distance over to the left. Both districts sit on the north bank of the Thames as you look on a map.

The second arm would be found a couple of weeks later on the 28th of September near Lambeth Road, on the opposite side of the Thames from Whitehall Road and the Pimlico district.

But it was likely the discovery of the torso which shook police to their core. On the 2nd October, only a few days after the left arm was found near Lambeth Road, a bundle of material – felt to be part of a black petticoat – tied together with string was found in the corner of an underground vault. The vault was part of a cellar, and the cellar was beneath the foundations of the brand-new construction site which would go on to become New Scotland Yard. Part of a body had been found on what would shortly become the home base of the police force, and had been left right under the noses of the workmen and labourers who were creating the building.

The arm found on the shoreline off Whitehall was able to be matched to the torso found in the vault at the New Scotland Yard site by lining up the right arm to the shoulder socket. In addition to this, a cord which had been tied around the top of the arm (before the arm was wrapped in newspaper and discarded) was matched to the cord used to fix the petticoat around the outside of the torso.

The final piece of this body would be found by an intrigued local news reporter, Jasper Waring, on the 17th October. Fascinated by the discoveries of unidentified body parts, he took his faithful canine friend (reports from the time state that it was a Spitsbergen breed) to the construction site where the torso had been found, under the supervision of a police officer. With the sniffing powers of his canine companion, he was able to make the discovery of what would be the final part to this particular body – a left leg, buried approximately five inches beneath a mound of turned earth, which had been severed above the knee. The leg was found between 8ft and 9ft from the location where the torso had been located.

Image 4: a map showing the locations where the Whitehall victim's remains were found

Dr Thomas Bond, police surgeon, was called to the construction site when the leg was discovered. His examination at the scene found it to be in an advanced state of decomposition, and led to his conclusion that the leg had been on the construction site for some time – approximately 6 weeks - with an estimated time of death being around the end of August of that year. The labourer who had been present with Jasper Waring and the police officer at the time of the discovery was able to confirm that the area of earth had been turned over no more than 8 to 10 weeks ago, so it was likely that the leg was added to the soil some time after this. It's entirely possible that the leg was left in the vault at the same time as the torso, which was discovered two weeks' prior.

If anyone is keeping count, the body parts discovered between 11th September and 17th October now include a right arm and shoulder, the left arm, the torso, and the lower half of the left leg. The head and the remaining limbs were never found.

Initially, newspapers speculated that the body parts had been placed in and around the Thames by local medical students as part of a prank, but this suspicion was soon dispelled.

An inquest was soon opened into the death of the victim, presided over by Coroner Troutbeck, with Dr Herbert of St Thomas’ hospital providing evidence relating to the assessment of the body. He, like Dr Bond, felt that the death was likely to have occurred in August, and went on to state that the victim was a woman, likely between 5ft 8in and 5ft 9in in height. It was felt that the victim was from what the newspapers described as the ‘unfortunate’ class, which was assessed by the dirt beneath the victim’s fingernails, the skin being rough and hard, and the indication that the hands were those of a hard worker, such as a household servant. It was also described by the press that the victim was a woman of a ‘dark complexion’, although it does not elaborate on this, and that she was around 26 years old at the time of her death.

Image 5: a newspaper's depiction of the remains of the Whitehall victim being taken to the mortuary from New Scotland Yard.

Several of the workmen from the New Scotland Yard construction site were called to give evidence on the discovery of the torso. The clerk of the construction site, George Erant, gave evidence that he left the site on the Saturday before the torso was found, but saw no evidence of it in the vault. A labourer, named as Mr Hedges, reported that he was likely the last person to enter the vault on that Saturday before the site closed for the day. He had gone into the vault to look for a hammer and gave the area a thorough search, including the corner where the torso would later be found, which was empty at the time of him looking. It was therefore concluded that the torso had been placed in the vault between the end of Saturday working hours and the 2nd October. The vault was reportedly left unlocked when not in use, meaning that anyone passing by the construction site could have entered the premises, although one would imagine that they would have to know of the existence of the cellar to go looking for it and also be somewhat familiar with its layout.

In the same trend as the Rainham mystery, the jury at the coroners’ court concluded a verdict of ‘found dead’. The cause of death, again, was unable to be ascertained, and the identity of the victim remained elusive. Without modern tools such as DNA in the 1800’s, identification was a far more difficult process. If fingerprints were not kept on record, or if the body was too decomposed to allow for fingerprints to be taken, this would leave only facial or dental recognition as options, which was impossible in both cases as the heads of the victims were never discovered. If the victim was of the lower class of society, as the investigators and doctors suspected, it may be that she had never been reported missing.

Poverty levels in Victorian Britain were exceptionally high, and the UK had been thrown into the centre of a housing crisis by the 1880s. Workhouses had been formed during the 19th century in a bid to provide housing, food and medical care to those who were able to work. However, the reality of these developments were far from the ideal written on paper. Appalling living conditions, malnutrition, the fast spread of disease, forced child labour and long working hours were common place, as were harsh punishment and a high mortality rate. Despite this, the workhouses were packed full and overflowing, contributing to a high level of homelessness. If the Whitehall victim had been a member of the workhouse, or had perhaps been forced onto the streets, there was every chance that her absence, sadly, wasn't recorded or noticed. If she had been in employment as a household servant, any action as a result of her disappearance would rely on the household staff or homeowner reporting this to the police.

It’s curious that it took such a long time for the leg of the victim to be discovered in the vault - surely a thorough search at the time the torso was found should have been completed to check for further remains nearby. If this had been completed at the time, the foot would have been found several weeks previously, and likely in a more intact condition. If labourers were routinely going into the vault during construction, one would have thought that the smell of decomposition would have alerted staff long before the discovery on 17th October. Although the leg was buried, it was not far down in the earth and it's possible that the smell of decomposition would still have been noticeable. On the other hand, if the leg wasn't in the vault when the torso was discovered, this means that the killer was brazen enough to return to the scene in the next days or weeks to leave further body parts.

Elizabeth Jackson

There would be another lull between the discovery of the Whitehall victim and the next body, although with the papers being full of news of Jack the Ripper, the discovery of unidentified body parts during this period easily disappeared within the pages. The next documented finding occurred on 4th June 1889 near Albert Bridge when three boys, who had decided to spend some free time bathing in the Thames, found an item wrapped in a bundle of white cloth. Upon unwrapping the parcel, they made a discovery so disturbing that they transported it directly to the nearest police station.

A local surgeon, Dr Kempster, examined the body part, determining it to be a left thigh which had been separated at the hip and knee, with visible finger marks on the flesh which had been inflicted prior to death. The white cloth was able to be identified as part of a female undergarment, and the name 'L.E.Fisher' was found to be written inside the fabric lining.

It was later the same day that a local labourer near George's Stairs at Horsleydown spotted another bundle washed up on the shore. Upon examining its contents, he was able to contact the police quickly by gaining the attention of a passing police boat, and the contents were able to be transported quickly for medical review.

Dr Bond, a police surgeon who also reviewed parts of the Whitehall victim, was called to examine the latest discovery. He identified it as the lower part of a female abdomen, and assessed that the victim was not long deceased. An article on the 'Casebook: Jack the Ripper' website reports that the doctor was able to identify that an operation had been carried out (possibly illegally) based on the findings of incisions in the abdominal flesh, an incision in the uterus and the discovery of an umbilical cord and placenta. Dr Bond was able to connect the two body parts found that day, confirming that they came from the same victim - this was supported by the police matching the material each body piece was wrapped in as coming from the same garment of clothing.

Unlike the Whitehall corpse, which was discovered several weeks after the victim was thought to have died, the Times newspaper reported on 5th June that, ‘in the opinion of the doctors the woman had been dead only 48 hours.’ This meant that, in this case, the police were only two days behind the potential murderer.

A couple of days later, a gardener working in an area of Battersea Park which was cordoned off to the public came across a foul-smelling package tucked beneath some shrubbery. Police were called, and the remains were transported to the surgery of Dr Kempster, who had examined the thigh found earlier in the week. He identified that the parcel contained the trunk of a woman with some of the organs (spleen, kidneys, some of the intestines and part of the stomach) still present, but all others removed through an incision in the centre of the trunk.

Dr Kempster would be kept busy on that day, as he would be called to Battersea police station in the afternoon to examine remains which had been removed from the river by a barge worker, who had attracted the attention of a police boat after finding that the parcel - wrapped in a skirt - contained part of a body. Dr Kempster duly examined these remains, which he found to be the upper part of the same trunk he had reviewed earlier that day. The arms had been removed at the socket of the shoulders, with the head also having been removed with an incision low down on the neck, close to the collar bone. Although a segment of the trachea could be located, the remainder was missing and the lungs had also been removed via an incision down the centre of the chest, in the same tactic used with the trunk. It could be ascertained, after this discovery, that the victim had light red hair through assessment of body hair.

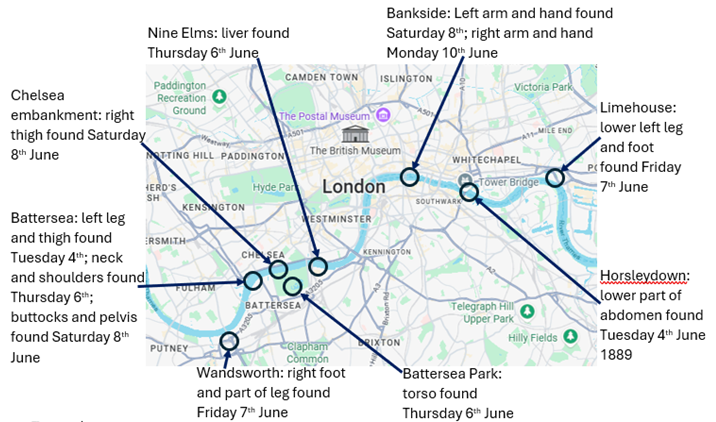

The Times newspaper would publish an update on the case on the 11th June 1889 with a comprehensive list of the body parts which had thus far been recovered. It stated: ‘Tuesday, left leg and thigh off Battersea, lower part of the abdomen at Horsleydown; Thursday, the liver near Nine Elms, upper part of the body in Battersea Park, neck and shoulders off Battersea; Friday, right foot and part of leg at Wandsworth, left leg and foot at Limehouse; Saturday, left arm and hand at Bankside, buttocks and pelvis off Battersea, right thigh at Chelsea embankment, yesterday, right arm and hand at Bankside.’

To make visualisation easier, I have mapped out the location where each body part was found, in addition to the day and date, on the map below. As you can see, the sites are much more spaced out than those in the Whitehall mystery and it was a much bigger task for the police to match each part to the same body. At first glance, it would be reasonable to think that the killer had dumped the body parts into the river Thames, and that the flow of the river had transported the parts to their discovery site. However, some of the discoveries were made away from the banks of the Thames - such as Battersea Park - so consideration must be given to the killer having travelled around the area depositing the bundles in which the parts were contained.

Image 6: a map showing the locations where the victim's body parts were found

In what could have been a morbid attempt at humour, or some sort of personal message, the perpetrator had thrown one of the body parts over the fence onto the Shelley estate, which was, at the time, home to Frankenstein author Mary Shelley.

Despite the head of the victim not being located, police were able to form a description of the victim through accurate reports from the doctors who collectively examined the body parts - the victim was assessed to be 5ft 5in with light coloured hair. After releasing this description to the public, a number of people came forward to report that the victim may resemble their missing loved one. One promising possibility was a missing barmaid by the name of Laura Fisher - not only did she match the physical description, but her name linked with the stencil of 'L.E.Fisher' inside the undergarment recovered with the body. However, she was located alive and well by police.

On 25th June 1889 the body was able to be identified as that of Elizabeth Jackson, who had been eight months pregnant at the time of her demise. Elizabeth was born and grew up in the local area, and was well known to the police in Chelsea. She had not been seen by family members since May of that year - something which was a cause for increasing concern for her father.

Ultimately, a scar on her wrist, the recovered clothing, and her pregnancy all contributed to police ascertaining the identity of the 24-year-old. Elizabeth worked as a prostitute in the London districts of Chelsea and Soho at the time, and boarded in a lodging house in Turks-Row, Chelsea, co-habiting with a man named John Fairclough. The police investigated the deceased’s partner but found that he had been away from London for several days before Elizabeth was thought to have been murdered. A nationwide search for the man commenced, with Fairclough not being traced until the beginning of July. He was located in Tipton St. John, East Devon, and subsequently transported to London to be questioned by police. He was believed to be the father of Elizabeth's unborn child, and Elizabeth had reportedly been posing as his wife by wearing a cheap wedding ring - at the time, having a child outside of marriage was heavily frowned upon and would have been considered quite scandalous. Fairclough reported that the pair had separated prior to her disappearance.

Police worked hard to trace Elizabeth's movements in the days prior to her death. They spoke to friends and acquaintances of the victim, and visited her regular haunts to speak to witnesses. She reportedly hadn't been seen at any of her regular locations for some time, and records showed that she had not been admitted to any local hospital or workhouse. Police considered that she may have left London, but this was a much more difficult feat at the time than it is today. Without the accessible network of buses, taxis, trains and cars that we have in the 21st century, and considering Elizabeth's financial position, police considered that the only way for her to have left London was on foot - something that they felt would have been extremely unlikely based on her advanced pregnancy.

Friends of Elizabeth informed the police that she often remained in Battersea Park after the gates had been closed and locked for the night - potentially a site where she would meet regular clients with the certainty that they would not be disturbed. As Battersea Park was the discovery site for part of the victim's body, this played into the consideration that she had been murdered and dismembered in the park, although any evidence of a scene indicating this violent act was not reported to police.

A coroner's inquest into the death was opened on 15th June - with the identity of the victim still not ascertained - under Dr Braxton-Hicks, with a quote from the 17th June stating: ‘the division of parts showed skill and design: not, however, the anatomical skill of a surgeon, but the practical knowledge of a butcher or knacker. There was a great similarity between the condition, as regarded cutting up, of the remains and those found at Rainham, and at the new police building on the Thames embankment.’ For anyone who may not be familiar, a knackerman was a worker who would collect deceased, or dying, animals and take them to the 'knackers yard', where the knackerman would recycle and preserve any usable parts of the animal, such as bones, fats, oils, and skin. This minimised the amount of wastage, but also provided materials for a variety of uses. It’s a job role that was widespread across the UK at the time, and is the origin of the phrase to ‘send something to knackers yard’ – meaning that it’s reached the end of the road.

At the inquest, it was confirmed that the foetus had been removed from the victim's body post-mortem. Although an illegal abortion had previously been considered as the cause of death, this was subsequently discounted - although the concept that the victim may have died as a result of some sort of illegal operation remained. The police considered that the remaining body parts - including the head - had been destroyed in a bid to prevent the identity of the victim, and therefore maintain anonymity for the surgeon who may have been involved. However, no evidence existed to back up this theory. The inquest was adjourned for two weeks, during which time the body would be formally identified.

When the inquest resumed on the 1st July, the public gallery looked considerably different. Now that the victim had a name and a face, the family of Elizabeth Jackson were present to hear the evidence brought forward by police and medical experts. Not only were her family present, but the tracing of John Fairclough meant that he was able to be placed on the stand to give a full account of his relationship with the victim, and his recollection of her movements when he had seen her last. His movements in the days before and after her death were confirmed by police, completely eliminating any involvement from her partner in her death.

Despite the police being able to identify the victim and link this death to the Rainham and Whitehall mysteries, the death of Elizabeth Jackson did not break any other trends in the Thames Torso murders. No evidence was found to explain how she had died, and a cause of death could therefore not be established at the time of the inquest. Likewise, there was limited information to explain how her remains had come to be in the river Thames, aside from the suspicion that she had been killed in Battersea Park.

As the inquest closed, the jury recorded a verdict of ‘wilful murder against some person or persons unknown’. Despite the police being only 2 days behind the killer at the time the remains were discovered, the suspect continued to elude justice.

The Pinchin Street Mystery

The final case included in the ‘canonical four’ occurred just a few months after the death of Elizabeth Jackson.

On 10th September 1889 at 5:15am, police constable William Pennett was on patrol in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel, when he came across the headless, legless torso of a woman beneath a railway arch, partially concealed underneath a blood-covered chemise. As in the cases previously, it was noted that the murder and dismemberment were likely to have occurred elsewhere – a small amount of blood was found on the ground at the scene, but this was though to have leaked from the torso after it had been deposited. Careful examination of the chemise was completed for any clues which may help to identify the victim, but no labels were noted and the chemise was found to be a commonly sold type.

Image 7: an artist's depiction of the discovery of the Pinchin Street torso with the media questioning if it relates to the work of Jack the Ripper

A local shoe shiner by the name of Michael Keating approached the police and advised that he had arrived beneath the railway arch between 11o’clock and 12o’clock the night before, as he normally slept in the archway adjacent to the one where the torso was found. (As mentioned previously, the level of homelessness in Victorian Britain at the time was very high - many people would find sheltered areas overnight before going to find work in the morning. Sadly, in most cases the wages still would not pay them enough to spend a night off the streets.) Mr Keating passed back through this archway a couple of times during the night, but did not notice anything on the ground and found nothing out of the ordinary until he was woken by the police constable at 6am, not long after the body was discovered. A further man, Richard Hawk, a sailor from St Ives, slept in the same archway as Michael, and arrived beneath the archway at twenty to four in the morning – he knew the time exactly, as he had asked a passing policeman. He also reported seeing nothing unusual.

During examination of the torso, the police surgeons noted bruising around the victim’s back, hip and arm, leading to the conclusion that she had been beaten shortly before her death, which was estimated to be within the 24 hours prior to the discovery of the body.

In tactics reminiscent of the Ripper, her abdomen was noted to be extensively mutilated, but no mutilation was found around the genitals, which had been a clear hallmark of the Ripper murders. For this reason, careful consideration by police ruled out this murder and mutilation as being caused by the Ripper - although, this didn't stop the press from agitating the public with rumours that the discovery could indicate a return of the Ripper after a hiatus.

The victim was thought to be between the ages of 30 to 40, but despite an extensive search of the area being carried out, no other body parts relating to this victim would be found to provide further information to aid identity. Pathologists were able to get a little closer to identifying a cause of death when they noted a lack of blood in the tissues and vessels of the torso. This led to them tentatively suggesting haemorrhage, or bleeding – either internally or externally – as a cause of death. However, without other body parts being found, it was impossible to identify the location of the fatal wound. Extensive mutilation to the abdomen did not mean that these wounds led to the death of the victim – evidence was, in fact, given at the inquiry which indicated that the abdominal cuts occurred post-mortem.

An inquiry was held by the coroners’ court, at which evidence was given both by the police and by the witnesses who had been sleeping rough under the adjacent railway arch. Aside from expressing some surprise that, despite the narrow window of time that the body could have been disposed in, no-one of suspicion was seen in the area, the coroner closed the inquiry with the jury’s verdict of ‘wilful murder against some person or persons unknown’. Those involved would consider whether the disposal of the remains within the Whitechapel area was a carefully considered move by the culprit in a bid to throw suspicion on the nameless, faceless Ripper, but this was purely speculation. The remains of the deceased would go on to be interred in a cemetery in the East London area.

The newspapers began to speculate as to the identity of this latest victim. They suggested that this could be the remains of a lady named Lydia Hart, who had been reported missing, but this theory was disproved when Lydia was found as an inpatient in a nearby hospital. Another missing girl in the area, Emily Barker, was put forward as a candidate, but later refuted when examination of the corpse deemed the remains to be of an older and taller woman than Emily. As such, the body would remain unidentified.

Extensive debates and deliberation were held between police at the time, and it was firmly felt that the Thames Torso killer was not Jack the Ripper, despite comments and articles published by the press. Despite the cases occurring around the same time, and overlapping in places, the differences in the way the crimes were committed were deemed to be too different. Jack did not dismember his victims and spread their body parts around the local area. In fact, it appeared that he took great pleasure in leaving his victims to be found in the manner in which he had left them - mutilated, and left as a spectacle for the unfortunate person who discovered them. The Thames Torso murderer, on the other hand, made some bid to conceal his crimes by carefully dismembering and disposing of the body parts. Perhaps he hoped that some of the remains would be transported down the Thames and out of the estuary mouth, never to be seen again. Perhaps he just hoped that the remains would be found weeks, or months, after their disposal, and that anyone who may have seen him discarding them would long since forget what they had witnessed.

Image 8: a further artist's depiction of the discovery of the Pinchin Street torso

It was concluded that two serial killers had been terrorising the streets of London, both of whom, ultimately, would disappear into the smoke and noise of the streets of Victorian London.

The police struggled from the very outset in the Thames Torso killings. The remains of each victim were scattered across districts of London, with the original site of each death never being located. Three of the victims were never identified. As such, the chances of finding any witnesses or creating a timeline of events were impossible, because where would one even start looking? No-one came forward to report finding a scene covered in blood, with the suspicion that something terrible may have happened. No-one came forward to say that they had seen someone throwing a suspicious package into the river. No-one came forward to say that a friend, spouse or relative had been acting in a manner that they would consider out of character, or unusual. If there were any witnesses, they either didn't know the importance of what they had seen, or they were too scared to make themselves known in the investigation. Perhaps the culprit committed his crimes in an area where suspicion was unlikely to fall, such as a butchery or, as mentioned above, a knackers yard. In locations such as these, the presence of blood would raise no concerns at all, and the killer need not worry about taking care in clearing up after committing his crimes. Previous suggestion has been made that Jack the Ripper could have worked in the meat trade based on his anatomical knowledge and his famous leather apron. It's not much of a stretch to consider that the Thames Torso murderer could have worked in the same field.

In comparison to the Ripper killings, which overtook the front page of every newspaper in London and sparked a morbid curiosity amongst the public of London, the Thames Torso murders were often relegated to the later pages - many of the articles that I’ve reviewed for information were page 5 and beyond. Why was this, when the whole of London seemed to be caught up in the whirlwind left behind each Ripper murder? It’s not unreasonable to think that the media would have jumped at the opportunity to throw another serial killer onto the front page, and yet the Thames Torso murders seem to be one of the lesser known cases in UK history.

From my own point of view, I think I need a little more convincing that the Thames Torso murders aren’t connected in any way to those committed by Jack the Ripper. There are certainly marked differences in how the bodies were found, but there are some similarities, too. Both killers were thought to be anatomically aware – Jack was well known for removing the intestines of his victims and leaving them on display. Elizabeth Jackson, like some of the Ripper victims, was resident of a lodging house. A dissected arm of one of the torso victims was noted to be decorated with tattoos – something that was far more unusual at the time than it is today – leading to police considering the possibility that the victim may have been a prostitute, like some of the Ripper victims. But aside from that, all of the murders were committed around the same area of London. Jack the Ripper committed his violent crimes in the area of Whitechapel, but several of the Thames Torso remains were found in close proximity to this – Chelsea, Pimlico, and Battersea. Like Jack, the Thames Torso murderer seemed to disappear after the Pinchin Street torso was discovered.

It's not outside the realm of possibility that the two could, at least, be connected. Perhaps they weren’t committed by the same person, as the police concluded, but is there the possibility that the two killers worked together or knew each other? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

I’d like to expand on the Thames Torso murders, though, because there’s every possibility that the canonical four aren’t the only victims of this serial killer.

The Battersea Mystery

Over a decade before the deaths of the canonical four, the bodies of two women would be found in what would be dubbed ‘the Battersea mystery’.

During the morning of Friday 5th September 1873, a policeman found the left side of a woman’s torso in mud verging the Thames outside the waterworks at Battersea. The Western Daily Press printed on the 9th September that this included ‘the left quarter of the thorax of a woman of fair skin and somewhat fat’ – a quote which was taken directly from the official report of the police surgeon at Battersea police station. Later that same morning, between 10am and 11am, the opposite side of the torso was found floating in the river at Nine Elms, and part of the lungs were found around about the same time beneath the arches of Battersea Bridge. Later that evening, the remaining part of the lungs were found in the water near Battersea railway. The final part of this body, which comprised of part of the face and scalp, would be found a day later just off the dockyard at Limehouse.

As you can see on the map below, all of the body parts found on Friday 5th September were located in quite close proximity, whereas the discovery of the scalp on Saturday 6th was quite a distance downstream. From this, it looks likely that the remains were thrown into the Thames either at Battersea bridge or somewhere just upstream of there. The part of the scalp, being found 24 hours later than the rest of the body parts, would have had longer to drift down the river and would therefore have travelled further.

Image 9: a map showing locations where the Battersea victim's remains were located

Over the following weeks, part of a leg, presumably the right, was located off the shore of Lambeth. This segment reached from the knee to the ankle. Part of the left leg was then subsequently found near Battersea, comprising of 6 inches below the knee. A pelvis would also be discovered at Woolwich. In the image to the right, I've circled the location of Woolwich, which is a considerable way downstream from Battersea and the location of most of the remains. However, as the pelvis was found much later than the other body parts, had they been thrown in the Thames, it would have had more time to travel.

Image 10: map showing Woolwich, London

During examination by the police surgeon, Dr Kempster, the body parts were assembled and it was assessed that they belonged to a female victim in her 40’s. The victim was noted to have pierced ears, dark, thin hair and dark eyebrows. Every effort had been made by the killer to make the victim unidentifiable, but features such as a scar on the left breast (likely from a burn), a mole on the right breast, and a mole on the neck had been left in place. The Western Daily Press, printed on 9th September, suggested that the short hair of the victim may indicate that she had recently been released from prison, may have suffered a recent illness, or may even have had her hair cut post-mortem to reduce the chance of identification.

In contrast to the canonical four in the Thames Torso murders, part of the head of this victim was located and could therefore be examined. A wound to the right temple was felt to have been inflicted shortly before death with a blunt instrument, leading police to conclude that they were definitely dealing with a murder inquiry – a murder which they concluded had happened within the 12 hours prior to the first body part being found. This put the time of death somewhere between late evening on Thursday 4th September and the morning of Friday 5th September.

Newspaper the Lancet reported at the time ‘contrary to popular opinion, the body had not been hacked, but dexterously cut up; the joints had been opened, and the bones neatly disarticulated, even the complicated joints at the ankle and elbow, and it is only at the articulations of the hip joint and shoulder that the bones have been sawn through.’ As with the canonical four, the killer had demonstrated a good knowledge of the anatomy - although whether this was from working with humans or animals remained a mystery.

The police searched relentlessly for any further body parts, focusing their efforts on the area between Battersea and Limehouse, and including searches of canal boats and vessels along that stretch of the river. A £200 reward was offered for any information relating either to the crime or to help identify the victim, but this would go unclaimed. As we have seen all too often by this point – although, bear in mind that this crime is over a decade before the canonical four – an inquiry returned a verdict of ‘wilful murder against some person or persons unknown’.

The unidentified victim would be laid to rest in Battersea cemetery on 21st September, without her hands or skull. Neither the killer nor the crime scene were identified.

Almost a year later, the second body in the so-called Battersea mystery would be discovered. The partly decomposed remains of a woman were found floating on the surface of the Thames in the region of Putney. There is a depressing lack of information about this victim, other than to say that the corpse was missing the head, both arms and one leg, and it also appeared that it had been treated with lime before being discarded in the river. Again, the jury at the inquest had no option other than to record an open verdict, as neither the victim nor the killer could be identified.

Image 11: map showing Putney, London

The two murders in the Battersea mystery are often included in publications relating to the Thames Torso murders, and it appears that many people have readily connected this case to those occurring between 1887 and 1889. Even though the two victims in the Battersea mystery died over a decade before, the similarities are paramount – not only based on the location that the body parts were found, but also the way that they were dismembered. It is, however, more difficult to draw as many similarities with the body found in Putney in 1874 purely due to a lack of available information on the case. The addition of lime in this case is also a significant difference.

Other possible links

In October 1884 near Tottenham Court Road, part of a woman’s body, including a skull with small amounts of flesh still attached, and a chunk of flesh from a thigh were found. Shortly afterwards, a woman’s arm, inclusive of a tattoo, was found wrapped in a parcel in Bedford Square. A few days later still, a police constable patrolling in the area of Fitzroy Square would make the gruesome discovery of a human torso wrapped in a parcel. Investigation at this scene narrowed down the deposition time of the torso to between 10am and 10:15am – a tiny window in which the killer could have been seen or caught. There is little information available in relation to this death, with the only conclusion drawn that the body belonged to a woman. The subsequent inquiry, like those we’ve discussed previously, would discuss the anatomical skill used in the dissection, but no other conclusions could be drawn and the case, ultimately, went cold.

Image 12: map showing the location of the Tottenham Court victim's remains

A case from the early 1900s is also mentioned alongside the Thames Torso murders. The crime in question was committed in 1902, with the victim being found in a small street called Salamanca Place, an area which has since been completely redeveloped. On Sunday 8th June, the remains of a woman were found in a gateway at approximately 4am by two workers from the Lambeth Pottery factory, which backed onto Salamanca Place.

The victim was found to be between the ages of twenty and thirty, and was estimated to be around 5ft in height with dark, straight hair. Her teeth were mentioned to be in good condition, although some recent damage was noted which suggested that she had been kicked in the face prior to her death. Some of her hair had been cut and skin had been removed from the skull, likely post-mortem in an attempt to prevent identification. The body was found to have been roughly cut into ten separate pieces, and this is where a key element differentiates this death from those of over a decade before – a doctor reported that the mutilation of the body indicated a complete lack of anatomical knowledge. More horrifically, parts of the body were found to have been boiled and baked, something which was not seen in any of the Thames Torso victims. At inquest, the police reported that they had been unable to find any information leading to an identification of the victim, and an open verdict was therefore reached by the jury.

It seems unlikely that a killer who was found to be so adept with knowledge of the anatomy would suddenly abandon their skills in this case. This murder occurred after the turn of the 20th century, more than a decade after the last known Thames Torso victim was discovered in 1889 - one would have thought that the killer's macabre skills in dismemberment and dissection would only have developed over time. Additionally, the remains of the previous victims were separated in carefully wrapped parcels and discarded in different areas – likely to reduce the chance of them being compared and reassembled – so why would the killer throw caution to the wind and dump all parts of this victim in a single pile, with the head included? Let me know whether you think that this case is linked, or whether you think there are too many differences.

I’m going to give the final, very brief, mention to a case which has been connected to the Thames Torso murders, but occurred across the channel in France. This is described in a 2002 book by R. Michael Gordon named ‘The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London’. An unsolved murder, named ‘Le mystere de Montrouge’ occurred in Paris in November 1886, where the torso of a woman was discovered on the steps of Montrogue church. The head, legs, right arm, left breast and uterus had been removed. Like the crimes committed in London, the victim was never identified and a suspect was not traced. Some feel that there is a potential link between this case and the London crimes, and it may not be beyond the realms of possibility – no torso victims were found in London in 1886, so where was the killer during this time? I wasn’t able to find very much information relating to this case at all, but let me know in the comments if you’ve heard of this link and what your thoughts would be.

It seems like a huge injustice to the victims of the Thames Torso killer that their deaths took a back seat in comparison to those committed by Jack the Ripper. Why did the Ripper cases grip so much of Victorian Britain when another killer was working away behind the smokescreen created by Jack? And what are your thoughts on the other cases listed outside of the canonical four? If the same killer was responsible for the murders in 1883 and 1884, what were they doing in the years between these murders and the next known victim? Could they have been abroad, or in another part of the UK? Are there other unsolved crimes for which the killer is responsible, scattered across the UK, or perhaps even Europe? And did the killings just stop, or did they continue elsewhere? After the 1889 Pinchin Street mystery, the Thames Torso killer - like Jack the Ripper - seemed to just disappear. It's no wonder that various historians question whether the killer could be responsible for other unsolved crimes.

The fact that only one of the victims could be identified feels unbearably sad – someone must have been missing their loved one, and yet no connections could be made to put names on each of the graves.

There are so many questions that it’s impossible to know the answer to – least of all, who the killer actually was. Justice was never served, and the stories of these victims, like those of Jack the Ripper, have been added to the history books with no resolution – the only difference is that Jack’s victims are still relayed in documentaries, podcasts and films to this day, whereas the Thames Torso victims seem to have been resigned to the back pages. Hopefully this post has brought some attention to these cases and to the victims who met such a sad and undignified end.

References for text:

The Thames Torso Murders | Crime+Investigation UK

Thames Torso Murders - Wikipedia

The Thames Torso Murders: Victorian London's Other Ripper - Historic Mysteries

Jack the Ripper - The True Crime Database Membership Jack the Ripper Whitechapel Murders

Casebook: Jack the Ripper - Daily News - 23 October 1888

Casebook: Jack the Ripper - Elizabeth Jackson

The Thames Torso Murders: Victorian London's Other Ripper - Historic Mysteries

Home | Search the archive | British Newspaper Archive

The Rainham Mystery. • | Weekly Dispatch (London) | Sunday 24 July 1887 | British Newspaper Archive

The Thames Torso Murders | Crime+Investigation UK

Woman - Unsolved Murder 1902 - Salamanca Place, Lambeth, London - Woman Unsolved Mysteries UK

Lambeth Horror. | Dundee Evening Telegraph | Thursday 03 July 1902 | British Newspaper Archive

Thames Torso Murders - Whitehall Mystery - Pinchin Street Torso

Credit for images:

Image 1: artists depiction of the discovery of one of Jack the Ripper's victims: Jack the Ripper | Identity, Facts, Victims, and Suspects | Britannica

Image 2: map showing location of Rainham victim's remains, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 3: map showing Whitehall in comparison to Whitechapel, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 4: map showing locations of Whitehall victim's remains, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 5: artists depiction of the Whitehall remains being taken to the mortuary: An epidemic of murder in late Victorian London – Historia Magazine

Image 6: map showing locations of Elizabeth Jackson's remains, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 7: an artist's depiction of the Pinchin Street torso discovery Thames Torso Murders - Whitehall Mystery - Pinchin Street Torso

Image 8: an artist's depiction of the Pinchin Street torso discovery pinchin-street-torso-found – History of Sorts

Image 9: map showing locations of the Battersea victim's remains, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 10: map showing Woolwich, London, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 11: map showing Putney, London, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Image 12: map showing locations of the Tottenham Court victim's remains, taken from Google maps, with endorsements by the author

Add comment

Comments