Wych Elm Bella

Disclaimer: this article contains details which may be upsetting for some readers. Discretion is advised.

The story of Wych Elm Bella is known not only across the UK, but across the world. It's been covered in newspaper articles right the way through from 1943 until today, and has been turned into plays, operas, television shows and films. It's been written about in many, many books and graffiti relating to the case is still occasionally daubed on walls near the scene where the body was found.

So why has the victim remained unidentified and the murder remained unsolved for more than 80 years? With so much extensive coverage, how has no-one found out who this female was and how she came to be in the hollow of a tree in the middle of a woodland?

In this case, we're not just going to look at an unsolved murder. We're going to be drawn into the worlds of witchcraft, spies and espionage in a bid to untangle the facts from the fiction.

Tucked away in the county of the West Midlands in England, hidden on the outskirts of the south-west of Birmingham, is a patch of forest known as Hagley Wood. The woodland sits just off the A456, and is today a stone's throw from both Hagley Golf and Country Club and 350-acre Hagley Park. To the south of the woods lies Clent Hills, an area owned and protected by the National Trust.

Back in 1943, Hagley Park - which sits around Hagley Hall - and neighbouring Hagley Wood were owned by the 11th Viscount Cobham. Today, the estate is owned by the 12th Viscount Cobham, but the woodland no longer forms part of this. Sections of land were sold by the 11th Viscount to pay for the escalating fees required to maintain the house and grounds, meaning that the property owned by the family today is much less than in the 1940s. Extensive conservation work has taken place throughout recent years, with Hagley Park and part of Hagley Hall now open to the public with the support of organisations Natural England and English Heritage. Photos on the Hagley Park website show a quiet, tranquil and restful area with no hint of the mystery which still hangs over the area.

The fact that Hagley Wood was privately owned back in 1943 would impact the actions of a group of teenagers who had crept onto the land to do some bird-nesting. This activity - searching for nests from which to raid eggs, subsequently selling them on - was popular at the time, even if it was frowned upon. Although the practice still exists today, laws are in place to prevent damage to the nests and birds as well as their eggs, threatening those who participate in such activities with legal action and even imprisonment.

The four boys in question - Robert Hart, Thomas Willetts, Bob Farmer and Fred Payne - spotted a promising looking wych elm tree with multiple branches extending from the main trunk to create something of a hedge, which they thought ideal for nesting birds.

Image 1: a map of the layout of Hagley Wood and surrounding areas

15-year-old Bob Farmer began an ascent of the tree ahead of his friends, picking his way through the limbs until he reached a gap in the trunk, finding the centre of the tree to be hollow from years of wood cutting. Peering in - hoping, no doubt, to find a quietly nesting bird - he was bewildered to see the pale outline and deep eye sockets of what appeared to be a skull. He reached an arm into the space and grasped the object, pulling it out into the light for a better look.

What he had initially suspected to be the remains of an animal was very clearly human - Bob would later describe: 'there was a small patch of rotting flesh on the forehead, with lank hair attached to it. The two front teeth were crooked.' The group examined it, disturbed by what they had inadvertently stumbled across.

Panicking, the four boys deliberated what to do. Terrified of the repercussions from the owners of the Cobham estate - and their own parents - if they made it known that they had been trespassing, they agreed to say nothing at all and to leave the remains where they were, perhaps in the hope that someone else would stumble across them and call the police. Bob Farmer climbed back up the tree, dropping the skull back into its hiding place, and the group - feeling more than slightly uncomfortable - went on their way.

For Thomas Willetts, though, the guilt at keeping such a huge piece of information quiet gnawed away at him, and he informed both of his parents of the skull tucked away in the wych elm tree. Instead of chastising their son for trespassing, his parents were quick in relaying the story to the authorities who headed to Hagley Wood to assess the situation themselves.

Following directions from the teenagers, police found the wych elm and discovered not only a skull but evidence of further remains tucked in the hollow of the tree trunk. Home Office pathologist Professor James M Webster was called to the scene, and team work between the pathologist and the police retrieved a near complete skeleton. The body was missing one of the hands, but an expansion of the search radius discovered this a short distance from the tree base, with police theorising that it had been dragged there by wild animals.

Image 2: a drawing printed in the paper describing the physical details of the body from the wych elm tree

Professor Webster arranged for the remains to be transported to his office in Birmingham for forensic examination. He assessed that the skeleton belonged to a woman, and had been in the tree for approximately 18 months prior to its discovery. A description was posted in the Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail on 24th April 1943 saying: 'her age is given as between 25 and 40, most probably 35, height 5ft, with light brown hair and dressed in dark blue and mustard coloured striped cardigan and mustard coloured skirt: blue crepe soled shoes, size 5 1/2. All the garments were described as poor quality, and a wedding ring found among the bones was of rolled gold, probably worth 2/6 [2 shillings and 6 pence, equivalent to less than £5 in modern money] to-day.' She was thought to have given birth at least once during her lifetime, and estimated to have died around October 1941.

Cause of death was difficult to ascertain due to the advanced level of decomposition, but a piece of taffeta found in her mouth indicated that she had suffocated. No physical injuries were noted, but a near-full dental profile was able to be obtained in a bid to aid identification, and the pathologist noted that the victim had had dental work completed in the year before her death. It was hopeful that, with such recent work having been completed, up-to-date dental records may provide them with information about their victim.

Police carefully investigated the tree, and found that the inner dimensions were such that the victim could only have been placed in the tree hollow whilst she was still alive or when her body was still warm, as the onset of rigor mortis would have prevented the body from fitting into the available space if she had been placed in there some time after death. Rigor mortis commences between one and two hours after death, generally affecting the smaller muscles of the body first, and (depending on environmental conditions) is fully established at twelve hours post-mortem. As the muscles become stiff, the lack of flexibility would have made it increasingly difficult to fit the victim into such a small space.

Despite a clear description of the victim's clothing being released to the public, a wedding band being found with the remains, and a good dental impression being obtained, the process of identifying the woman from the wych elm was difficult. She had been discovered during 1943 amidst the height of World War II, with nearby Birmingham being a key target for Luftwaffe bombing. The number of people reported missing was enormous, and the quantity of people being called up for war service meant that authorities had fewer staff to follow up on reports.

In excess of 3,000 missing person reports were trawled through in a bid to find details which matched the description of the wych elm victim, but no leads were found. Police contacted dental practices locally at first, but then extended their search nationally, hoping for a response with a match to the dental impression they held for the deceased woman. This, too, proved unsuccessful.

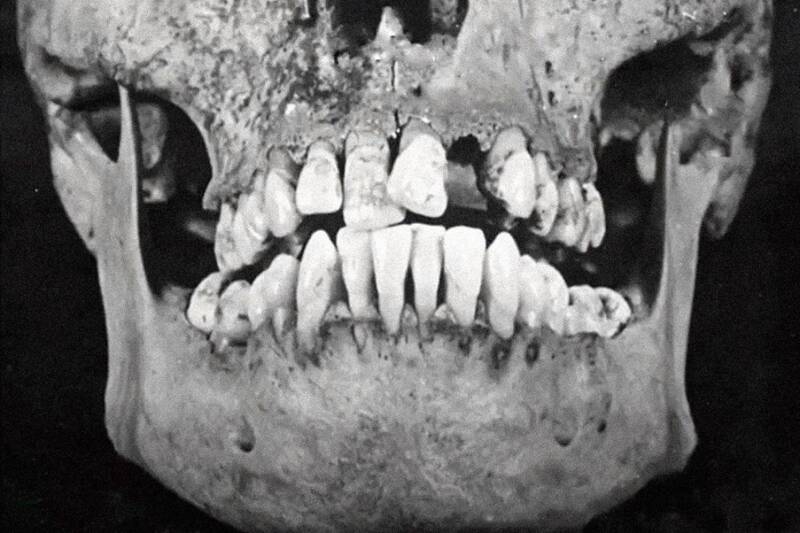

Image 3: side view of the skull of the body from the wych elm tree

Image 4: front view of the skull of the body from the wych elm tree, showing the layout of her teeth - in particular, the two crooked teeth on the top

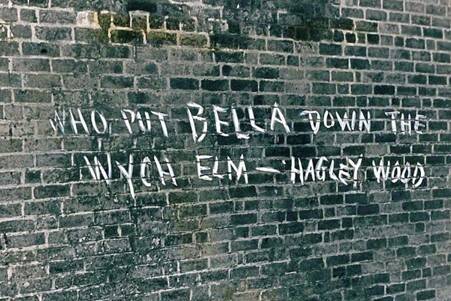

The press, who had reported feverishly about the body discovered on the Cobham estate, eventually lost interest as information about the woman dried up and police failed to make an identification. This was until December 1943, when a series of bizarre graffiti started appearing in the area around Hagley Wood, peaking the interest of newspapers both locally and nationally.

The first of the graffiti - written in chalk - was found in Hayden Hill Road and read 'who put Lubella down the wych elm?' For some time, this odd sentence made little sense to local residents and wasn't connected to the body found in Hagley Wood until a second piece of writing was found on the wall of a deserted property on Upper Dean Street in Birmingham. This one asked 'who put Bella down the wych elm, Hagley Wood?' The more specific details caused passing residents to join the dots, leaving little doubt what it related to.

The graffiti did more than vandalise property. It gave police their first potential lead in months - after all, no-one had mentioned the name Bella (or Lubella) since the discovery of the body. Did someone know something, and had decided to taunt police? If they didn't, where had the name come from? After examining the scrawled writing and assessing that the sentences were written too far up the wall to be a prank by schoolchildren, authorities opted to take the graffiti seriously and started reviewing missing person reports for anyone by the name of Bella.

Any hopes which may have come from this were soon dashed, however, when no reports for anyone of that name surfaced. They went so far as to start taking samples of handwriting from local residents to compare to the graffiti in a bit to find the mystery writer and assess how much they knew about the case.

Even though no formal link could be found to indicate why that name had been included in the graffiti, the body in Hagley Wood became informally known as 'Bella' - a name which still sticks with the case today.

Possible Leads

'Bella'

With no formal identification of the body, chances of finding out who was responsible for the murder was nearly impossible. As a result, the case went cold as focus turned back to war efforts.

A possible link was established in 1944 when a sex worker approached police to report that a fellow prostitute, who worked the Hagley Road area of Birmingham, had disappeared some three years earlier in 1941. The reporter knew the woman only as 'Bella'. With the graffiti still being fresh in the minds of police, lines were drawn between the Hagley Wood body and the new missing person report. However, the length of time which had elapsed between the prostitute last being seen and the report being made gave little to work on, and no further progress was made.

In 1949, police were informed of the Hagley Wood area being frequented by groups of gypsies across the last decade. People even reported having heard screaming in the woodland around the time the wych elm victim was thought to have died. It's unclear if this was the first the police had heard of this, or whether reports had been made previously but vanished in the activities of the second world war. Was it possible that 'Bella' could have been a member of the gypsy community?

Clara Bauerle

Some time after the war had ended a number of MI5 files were declassified, leading to an interesting theory in the case of Wych Elm Bella.

One particular file discussed the case of the execution of a confirmed Nazi spy - a death which would be the last one to take place in the Tower of London. The man in question was Josef Jakobs, an agent in the intelligence department of the German Army. He had been dispatched to the UK during 1941, parachuting into Huntingdonshire under cover of darkness in an attempt to stealthily enter the country. This attempt failed, however, when he broke his ankle during the landing and was apprehended by the local Home Guard the following morning, still wearing his flight suit.

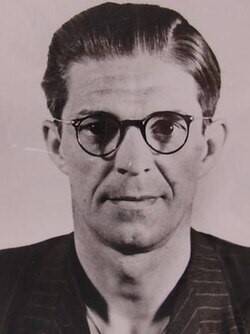

Image 5: Josef Jakobs

A search of his pockets and personal effects found £500 in British currency (equivalent to approximately £19,700 today), forged identification papers, a radio transmitter, and - for reasons unknown - a German sausage. The final item found on his person was a photo of a German Cabaret singer named Clara Bauerle, who Jakobs identified as his girlfriend. Under questioning, he said that she had also trained as a spy for German Intelligence, and the plan had been for her to follow him across to England after he radioed their department to advise that he had arrived undetected. This radio communication, of course, was never made by Jakobs, with the man telling his interrogators that he did not believe Clara would be sent over now that he had been arrested.

Jakobs was transferred to Brixton Prison Infirmary for treatment of his broken ankle after providing a statement at Cannon Row Police Station, London. He was detained for a further two months after his capture before he stood trial in front of a military tribunal in August 1941, where he was ultimately found guilty of spying. He was sentenced to death by firing squad at the Tower of London - a sentence which was carried out at 7:12am on 15th August 1941. He was buried in an unmarked grave in St. Mary's Catholic Cemetary in Kensal Green, London.

The story of Josef Jakobs is, in itself, a fascinating tale, and the surface has barely been scratched here. However, when the records were released it provided speculation amongst those who remembered the story of the female body found in the wych elm in Hagley Wood. Jakobs had told MI5 that his intended destination had been Birmingham. The city was a significant target for German bombers due to its high level of munitions factories, and successful attacks on these would reduce the quantity of munitions provided to Allied forces. As a result, it was a popular destination to send Abwehr spies and a network of German Intelligence was established in the area with the aim of extracting information about the munitions operations.

Clara Bauerle, Jakobs said, had been selected as a spy because she had previously worked in Birmingham before the outbreak of World War Two as part of a Cabaret show, and had perfected a Birmingham accent. This made her an excellent candidate to send over to England, with the anticipation that she would blend into the community and be able to gain the trust of locals. Those keeping track of the Hagley Wood case therefore asked - was there a chance that Clara had been sent over, even though a message from Jakobs hadn't been sent? Did she perhaps land in the wych elm and get stuck, or obtain unsurvivable injuries and pass away there? Any record of Clara Bauerle in Germany reportedly ceased during 1941, which supported the theory that she had left the country and fuelled the fire for those who considered her a candidate for the body in the tree.

Image 6: Clara Bauerle

This theory was, over time, debunked. Clara was 6ft tall - a full foot taller than Wych Elm Bella, meaning that she differed significantly from the physical description. If she had parachuted into the area, there would have been evidence of the parachute remains somewhere. Even if she had climbed into the tree voluntarily - such as to hide from a passer-by - why would she not have climbed back out again when the coast was clear? How did she end up with taffeta stuffed into her mouth? And why was she wearing a cardigan and skirt, clothing which surely wouldn't have been suitable for jumping from a plane?

Years passed with no information regarding Clara until records were uncovered showing that she had died in a Berlin hospital on 16th December 1942. Perhaps her role as a spy had kept her off of official records in Germany until her death was recorded, but this put an end to suspicions over whether she had, in fact, made it to England.

Witchcraft

Anthropologist and archaeologist Margaret Murray, who worked at King's College in London during 1945, provided one of the earlier witchcraft theories relating to the body found in the wych elm.

Murray cited the significance that the wych elm holds in the world of the occult, and also talks about how the removal of one of the hands is part of an occult practice called the 'Hand of Glory'. The hand is generally dried for future occult purposes, or sometimes baked, with the melted fat being used to make a candle - a disturbing practice which sounds more like it belongs in medieval times rather than the mid-1940s.

The press, attracted as always to an outlandish theory, caught on to the suggestions of Margaret Murray. With some journalistic research they connected the case of wych elm Bella to that of the murder of Charles Walton, who had been attacked in the village of Lower Quinton just 35 miles from Hagley Wood on 14th February 1945.

Charles lived with his niece Edith, whom he and his wife had adopted when Edith was just three years old. After the death of Charles' wife in 1927, Edith had continued to live at 15 Lower Quinton with Charles, who paid her a housekeeping fee each week. Charles had worked in agriculture throughout his life and had always resided in Lower Quinton. After the onset of rheumatism, he reduced his regular job to undertake casual agricultural work in the area, and had been working for local farmer Alfred Potter for the nine months prior to his murder.

When Charles failed to come home from a day's work slashing hedges on the farmland, 33-year-old Edith alerted neighbour Harry Beasley, who walked with her to Alfred Potter's farm. The three of them walked to the field where Charles had last been seen, and were horrified to discover his body a short distance from where he had been working. He had been beaten around the head, had his throat cut, and the killer had pinned him to the ground by inserting the prongs of a pitchfork through either side of his neck, and a slash hook through his throat. There are mixed reports on whether a cross had been carved into his chest - it's possible that this point had come from subsequent rumours and gossip circulating around the case.

Image 7: Charles Walton as he was found

Talk of witchcraft in the case of Charles Walton began when a story was unearthed in a locally-written book named 'Folklore, Old Customs and Superstitions in Shakespeare Land'. One of these stories included a young plough-boy named Charles Walton, who had been walking home across the fields in 1885 when he reportedly met a phantom black dog (as any Harry Potter fan will tell you, this is a superstitious omen of death). This encounter wasn't to be a one-off, however - Charles met the same dog several nights in a row, with it being accompanied by a headless woman on the final night. Later that same evening, Charles received the information that his sister had passed away.

Even though there was no evidence to suggest that the Charles Walton in the book was the same Charles Walton who had been brutally killed, gossip circulated that some of the locals had always believed Charles Walton to be a witch. Some reported that they knew him to have cast the 'evil eye' and had cursed the crops of local farmers, citing the failure of crops in 1944 as evidence. It was believed that these practices led him to be killed in a manner which was symbolic in witchcraft circles, as letting his blood soak into the earth was believed to replenish the fertility of the soil and therefore prevent the failure of future crops.

Dr Margaret Murray fuelled this theory when her opinion was printed in The Birmingham Post in 1950, saying: '"I think there are still remnants of witchcraft in isolated parts of Great Britain. I believe that Charles Walton was one of the people sacrificed. I think this because of the peculiar way in which he had been killed. His throat had been cut and a pitch-fork had been used after he was dead to prevent him from being moved. I am not interested in the murder, only in the witches. I think it was a murder without normal motive - no money was missing and there was no other reason why the old man should have been killed. He died in February, one of the four months in the year when sacrifices are carried out."' When questioned about Wych Elm Bella, she said: '"I believe the dead woman here was another victim of the devil-worshippers."'

Sound bizarre? The police clearly thought so. Scotland Yard were drafted in to help search for Charles Walton's killer, as such violent acts rarely happened in the rural area and local police requested help with the investigation. Suspicions fell not on witchcraft, but on a local prisoner-of-war camp which was housing Italian detainees at the time. Inquiries found that the camp residents were able to come and go around the local area as they pleased - they were required to attend scheduled work, but there was no requirement for them to sign in and out of the camp, or keep a record of where they had been during the day. Alfred Potter fell under suspicion for a period of time, but Charles' case has ultimately never been solved.

Letters to the Press

With rumours of witchcraft ticking away in the background, journalist Wilfred Byford-Jones wrote an article in the Wolverhampton Express and Star newspaper in 1953 under his pen-name 'Quaestor'. Although the article itself held no huge significance, the response he received did.

A letter was sent to the paper in response to the printing of Byford-Jones' article, signed from 'Anna of Claverly'. In an echo to the reports of Josef Jakobs, the writer said that the woman in the wych elm had been involved in a Nazi spy ring which had been operating in the Birmingham area during the 1940s. 'Anna' wrote: 'finish your articles re the Wych Elm crime by all means. They are interesting to your readers, but you will never solve the mystery. The one person who could give the answer is now beyond the jurisdiction of the earthly courts. The affair is closed and involves no witches, black magic or moonlight rites.'

Although some initially suspected Byford-Jones of penning the letter himself for publicity, this was put to bed when 'Anna of Claverly' was unveiled as Una Mossop.

Una told the journalist that her former husband, Jack Mossop, had worked in one of the many munitions factories across the West Midlands during 1940. Although he kept it hidden from her at the time, he had become acquainted through his work with a Dutchman he called van Raalte. He had provided Jack Mossop with a sum of money, perhaps to gain his loyalty or trust. Jack would eventually confess to his wife that he had been passing the Dutchman information relating to the munitions factory and its business, and he knew the Dutchman to be handing this information on to officials in Germany. Una would later tell police that Jack always seemed to have a considerable amount of money after meeting the Dutchman, and had made the assumption that van Raalte was involved in espionage.

During the confession to his wife, Jack told her that he had arranged to meet van Raalte at a pub near Hagley Wood one evening to discuss business. Upon arrival, however, he found van Raalte to be arguing with a Dutch woman who he did not name. With the argument drawing attention in the pub, van Raalte asked Jack to drive the pair to Clent Hill, an area near to Hagley Wood. Whilst Jack was driving, the argument in the car escalated and became violent. Jack heard van Raalte strangle the female in the back of the car, after which Jack assisted in the disposal of her body in the wych elm, saying that he feared the same would happen to him if he refused to help the Dutchman. It's not clear from the story whether the hiding place was suggested by van Raalte or by Jack Mossop.

Una told Byford-Jones that her husband's mental health had deteriorated throughout 1941 until he was institutionalised in 1942 after experiencing recurrent dreams and hallucinations of a woman's face watching him from inside a tree. He died whilst admitted to the facility on 15th August 1942, with his death certificate listing contributing factors as 'cerebral softening', 'myocardial degeneration', 'chronic nephritis' and 'acute confusional insanity'. Jack was reportedly a very heavy drinker, and had experienced a number of head injuries during one of his earlier jobs.

Byford-Jones passed all of the information he had accumulated to the police, who looked carefully at the claims. They were able to verify some of the details provided by Una Mossop but not all of them. If the timeline of events given by Jack in his confession to his wife were accurate, it matched the estimated time of death of Wych Elm Bella. MI5 became involved during the investigation, but neither the police nor the intelligence team were able to trace the Dutchman whom Jack had called 'van Raalte'.

Multiple questions surrounded the letters sent by Una Mossop to Byford-Jones. Why had she decided to speak out in 1953, a decade after the body in the wych elm had been discovered? Was it to maintain her loyalty to her deceased husband? If he had died in 1941, there was no way he would ever stand trial for the crime. And despite all of the information put forward by Una, the name and identity of Wych Elm Bella still remained elusive.

Image 8: a clip from a newspaper article in 1949

The case retreated into the background somewhat, but rumours and theories continued to swirl in the decades after the body in the wych elm was found, although none provided any leads or answers in the case. Speculation was fuelled by the occasional appearance of graffiti in the area around Hagley Wood and the south-west side of Birmingham, refusing to let the case disappear into the history books. Some of this graffiti even appeared several miles away in Wolverhampton - could it have been the same person writing it, or had other people decided to join in as a prank of what they felt to be a bit of a laugh?

Journalist Donald McCormick reignited national interest in the case by writing a series of articles in the Birmingham Daily Post in 1968, culminating in him releasing a book titled 'Murder By Witchcraft'. On the topic of the witchcraft theory, he described the reputation of Hagley Wood as being 'a haunt of witches covens', expanding to state 'there was an ancient tradition that the spirit of a dead witch could be imprisoned in the hollow of a tree and thus prevented from wreaking any more harm in the world.' He didn't dwell on the witchcraft theory, though, and delved into multiple different opinions and suggestions on how the body came to be in the tree.

Due to the declassification of wartime intelligence information, McCormick had been able to obtain information relating to German Intelligence during the 1940s, some of which bolstered the hypothesis that wych elm Bella had been involved in a Nazi spy ring. However, he also discussed the possibility that Bella could have been a refugee from the blitz in Birmingham - as we've already discussed, the city was a huge target for German bombing during World War Two, and the potential that she may have escaped to the outskirts of the city for safety was considered. McCormick wrote: 'the police thought it was more probable that she was a refugee from the blitz, for many people fled Birmingham when the German air raids came and some had been known to shelter in Hagley Wood.'

Throughout the process of his research, McCormick stumbled across a spy by the name of Lehrer, who was confirmed to have been operating in the West Midlands during 1941. He had a Dutch girlfriend called Clarabella Dronkers. McCormick considered the likelihood that the name Lehrer was an alias, and further research uncovered details of the execution of a Nazi spy named Johannes Marinus Dronkers who was captured in 1942 and put to death at Wandsworth Prison. The theory that the victim may have been Dutch would have explained the lack of physical evidence uncovered by police in the UK - any dental or medical records, in addition to identity papers, would have been kept in the Netherlands. The fact that Wych Elm Bella wore a wedding ring added weight to the possibility that she could have been Clarabella Dronkers. McCormick suggested that the victim may have been killed for risking exposure of the Nazi spy ring, or perhaps for having an affair with another man.

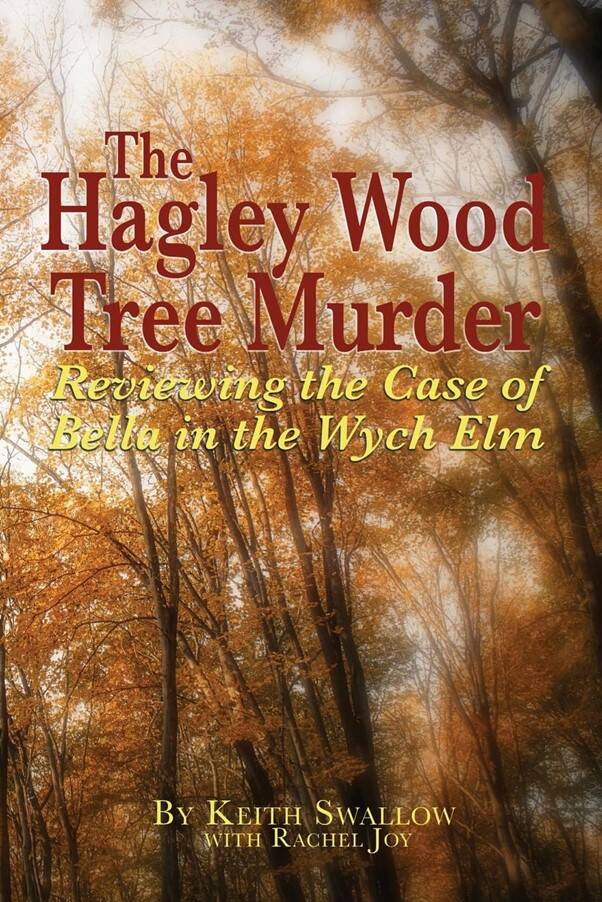

Perhaps the most realistic suggestion as to the identity of Wych Elm Bella came from author Keith Swallow in 2019. The then 59-year-old former Highways England employee penned a book about the wych elm case, which was at the time waiting to be published, called The Hagley Wood Tree Murder. He considered that the killing was more likely to be a result of a domestic incident, rather than related to a Nazi spy ring or witchcraft. As some of the locals around Hagley Wood reported, the area was popular with gypsies and the travelling community who would have become accustomed to the layout of the area - perhaps knowing of the hollow in the wych elm tree. Additionally, medical records for individuals would have been sparse due to the transient way the community lived, reducing the possibility of police tracing information. Was it possible that Bella was killed by a husband or partner, then her body disposed of in an area the culprit knew of and doubted people would ever look?

Keith Swallow questioned whether it would have been likely that a member of a Nazi spy ring would know the intricate layout of Hagley Wood to the point that they would know the best location to dispose of a body, and whether they would have gone to the trouble of driving out to the area. It was much more feasible that the site would be the chosen location for someone who knew the area intricately.

Image 9: the front cover of Keith Swallow's book

In relation to the graffiti, Swallow found that a popular song during the 1940s was Bella Bella Bambina, which could have been in the mind of the person writing on the walls. Swallow seems to indicate that the graffiti was the work of a pub-goer, as the chalk used matched the type kept in local establishments and could easily have been hidden in someone's pocket as they left after a few drinks. He added that members of the travelling community visited the pubs and there were several reports of violent incidents in the area.

Swallow said: '"much of what has been written is based on supposition or perceptions which are not backed by anything relating to fact. Inevitably, much of what has passed into the public domain is flawed. It is a case which has grabbed the attention of not only those within the local area, but others all over the world. However, some alarming inconsistencies exist in accounts which have been published in the intervening years, and there are some glaring errors within what has been presented as fact. My book debunks a number of the most popular theories. What it also does, for the first time, is draw on contemporary police files, newspaper accounts of the time and genealogical research to separate facts from fiction."'

Giving a face to the victim

Image 10: a facial reconstruction of the woman found in the wych elm tree

For more than 70 years between 1943 and the late 2010s, Wych Elm Bella had remained nameless and faceless. No-one knew what the victim looked like, as the level of decomposition at the time she was found meant that there were no remnants of her facial features aside from some hair.

This changed when Professor Caroline Wilkinson, who worked in craniofacial identification at Dundee University and had recreated the face of King Richard III after his remains were recovered from beneath a car park, was given the task. She had very little to work with - the remains had been kept in a police museum in the West Midlands for several decades after they were uncovered, but went missing somewhere around the 1960s or 1970s. West Midlands Police released a statement reflecting this, saying: 'searches have been conducted by the Police Museum volunteers and they have confirmed that we hold no exhibits, and can find no documentation, that may relate to this case at either of the West Midlands Police Museums. Additionally, searches were carried out by our Force Records Team, who have confirmed that there is no relevant documentation held with the major investigation team or in external storage.'

In short, no-one knows where the remains of Bella are. Not only does this mean that DNA cannot be extracted from the remains to add to the DNA database for future comparison, but it meant that Professor Caroline Wilkinson did not have a physical skull to use in her recreation, and had to utilise information from historic photographs.

Finally, after more than seven decades, an indication of what Wych Elm Bella may have looked like was released. Of course, it would do little to help with identification by that time - many people who may have recognised the victim were likely to have passed away themselves or be well into their 80s or 90s. However, it somehow gave the victim some added dignity and helped in the humanisation of her story - she stopped being just a photo of a skull and a story in the newspapers, and became a human being, even if her name and background remains unknown.

Where is the case now?

The case of Wych Elm Bella sits in the same position today as it did in 1943, more than 80 years ago. No-one knows her name. No-one knows where she came from, or her story. And no-one knows why she was killed and stuffed into the hollow of an old tree.

That doesn't mean that Bella has been forgotten. Right up until present day, her tale has been the subject of books, television programmes, films and even operas - the most recent being a theatrical documentary which was performed in 2024. In 2023, the BBC appealed for help in locating Bella's remains as part of a podcast being recorded by the corporation at the time called The Body in the Tree. Her story is of such interest that West Mercia Police completed a review of the case in 2014 and, when no further progress could be made, moved the full six boxes of case material to Worcestershire Archives where it is available for viewing by the public.

Image 11: graffiti on the Wychbury obelisk in 2006

Image 12: earlier graffiti in the area around Hagley Wood

Perhaps the interest from the public has come from the number of elements involved in the case - not only an unidentified body in a tree, but anonymous and mysterious graffiti, talk of witchcraft, and rumours of a Nazi spy ring. It sounds more like the plot of a film than a real-life murder mystery.

In reality, the chances of finding out who killed the victim are slim. The culprit is surely long since deceased themselves, taking their motive to the grave and living the rest of their life without facing justice. Perhaps the only thing which can be hoped for is that the remains may, someday, be found tucked in the back of an archive room or storage unit. Maybe there would be a chance of taking DNA to try to trace an identity for the victim through the route of familial matching, but at the very least she could be given a proper burial and resting place.

Conclusion

There is seemingly endless literature and documentaries available about Wych Elm Bella if you feel like taking a deeper dive into this tale, as I feel like I've barely scratched the surface in this post. I'd be interested to hear your thoughts in the comments, and what your opinions are on the many, many theories put forward by different people over the years.

The very last thing I'd like to mention is that this post isn't about witchcraft or Nazi spies. This post is about a woman who was killed or left to die in the middle of an isolated woodland on the outskirts of Birmingham, undiscovered for eighteen months. Before her death she was a living, breathing human being - perhaps with her own family, and most certainly with her own story to tell. She had a future and potential which went unfulfilled. The pathologist assessed that she had given birth during her lifetime, so there's every chance that a child grew up missing their mother.

We may not know the victim's name, but we know that she didn't deserve to meet the end that she did. Behind the fascinating facts and theories of the wych elm case, behind the stage plays, books, blog posts, archives, documentaries and podcasts, there is a victim who should be remembered.

References for text:

The Mystery of Who Put Bella in the Wych Elm? - Historic Mysteries

Who put Bella in the wych elm? - Wikipedia

The Hagley Woods Mystery: Bella in the Wych Elm | The Unredacted

Revealed after 75 years: The face of Bella in the Wych Elm - Birmingham Live

Christopher Lyttelton, 12th Viscount Cobham - Wikipedia

Killing of Charles Walton - Wikipedia

Musing No 2 - by Dr Angie Sutton-Vane

Bella in the Wych Elm - The Story of Jack Mossop - Josef Jakobs - 1898-1941

Credit for images:

Image 1: Hagley Wood map from The Birmingham Daily Post on 21st August 1968 The British Newspaper Archive Blog Who Put Bella Down the Wych Elm? | The British Newspaper Archive Blog

Image 2: drawing from the newspapers, printed in The Birmingham Daily Post on 20th August 1968 The British Newspaper Archive Blog Who Put Bella Down the Wych Elm? | The British Newspaper Archive Blog

Image 3: side view of the skull Who put Bella in the wych elm? - Wikipedia

Image 4: front view of the skull The Hagley Woods Mystery: Bella in the Wych Elm | The Unredacted

Image 5: Josef Jakobs Josef Jakobs - Wikipedia

Image 6: Clara Bauerle The Hagley Woods Mystery: Bella in the Wych Elm | The Unredacted

Image 7: Charles Walton The Charles Walton Witchcraft Murder - Historic Mysteries

Image 8: newspaper clip from The Birmingham Daily Gazette on 4th October 1949 The British Newspaper Archive Blog Who Put Bella Down the Wych Elm? | The British Newspaper Archive Blog

Image 9: front cover of book by Keith Swallow The Hagley Wood Tree Murder: Reviewing the Case of Bella in the Wych Elm: Amazon.co.uk: Swallow, Keith: 9781789633535: Books

Image 10: facial reconstruction Revealed after 75 years: The face of Bella in the Wych Elm - Birmingham Live

Image 11: Wychbury obelisk graffiti Who put Bella in the wych elm? - Wikipedia

Image 12: Hagley Wood graffiti The Hagley Woods Mystery: Bella in the Wych Elm | The Unredacted

Add comment

Comments